You might not be sure you saw what you think you saw when the first firefly of the evening shows up. But if you stare in the direction of the flicker of light, there it is again – the first firefly of the night. If you’re in a good firefly habitat, soon there are dozens, or even hundreds, of these insects flying about, flashing their mysterious signals.

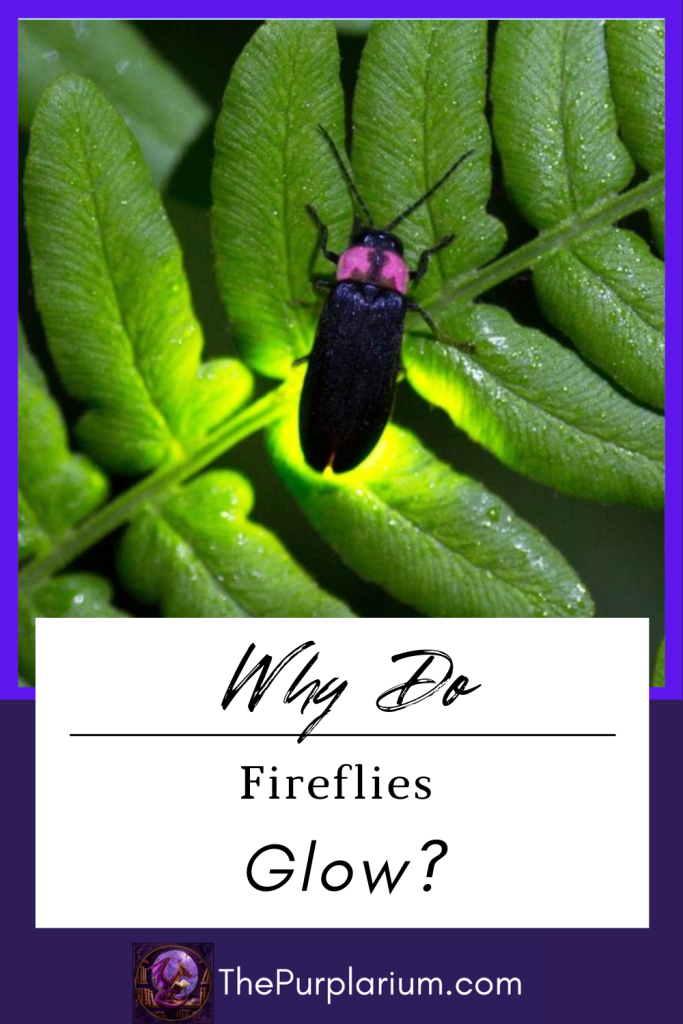

Fireflies, also known as lightning bugs, are not flies or bugs. They are soft-winged beetles related to click beetles. The most dramatic aspect of their biology is that they can produce light. This ability, called bioluminescence, is relatively rare in living organisms.

Bioluminescence

Fireflies produce light in special organs in their abdomens by combining a chemical called luciferin, enzymes called luciferases, oxygen, and ATP, which is the fuel for cellular work. Scientists think fireflies control their flashing by regulating how much oxygen goes to their light-producing organs.

Fireflies probably evolved the ability to light up as a way to ward off predators, but now they mostly use this ability to find mates. Interestingly, not all fireflies produce light. Some species fly during the day and rely on pheromones to find each other.

Each firefly species has its own signaling system. In most North American species, males fly around at a specific height, in the right habitat, and at the right time of night for their species, flashing a signal unique to their kind. The females watch from the ground or in vegetation. When a female sees a male making her species’ signal, she flashes back with a signal of her own. Then, the two signal back and forth until the male finds the female, and they mate.

A common backyard species, Photinus pyralis, also known as the Big Dipper, is a good example. A male flies at dusk about 3 feet off the ground and makes a one-second flash every five seconds in the shape of a “J.” The female sits in low vegetation and, if she likes what she sees, she waits two seconds before making a half-second flash of her own at the third second.

Some species may “call” for many hours a night, while others flash for only 20 minutes right at dusk. Some species have multiple signaling systems, and some might use their light organs for other purposes. Some male fireflies synchronize their flashes when many are around, like Photinus carolinus in the Appalachian Mountains and Photuris frontalis in places like Congaree National Park.

Scientists think these males synchronize so everyone has a chance to look for females and for females to signal males. These displays are spectacular, and many people want to see them, sometimes requiring a lottery for viewing permission. However, these species occur over wide geographic ranges, so you might see them in less crowded places.

They Can Defend Themselves – Stinkily

Many fireflies protect themselves from predators with chemicals called lucibufagins. These chemicals are similar to the toxins toads exude on their skin. While toxic in the right doses, they are also extremely distasteful. Birds and other predators quickly learn to avoid fireflies. I once watched a toad eat a firefly and then promptly spit it back out; the insect walked away, gooey but unharmed. A colleague of mine once put a firefly in his mouth – and his mouth went numb for an hour!

Many other insects mimic fireflies to look like something unpleasant to eat and poisonous. Some fireflies produce other defensive chemicals, too, contributing to their distinctive smell.

Some Photuris fireflies can’t make these defensive chemicals, so the females mimic the flashes of female Photinus fireflies and then eat the males that respond. These “femme fatales” use the lucibufagins they get from eating their prey to protect themselves and their eggs from predators. They quickly transfer the chemicals to their blood and spontaneously bleed if a predator grabs them.

Their Homes Are Critical

Most fireflies are habitat specialists, using woodlands, meadows, and marshes. They rely on undisturbed habitats to complete their lifecycles, which can take a year or more. Fireflies spend most of their lives as larvae preying on earthworms and other animals in the soil or leaf litter. Most adults don’t feed at all. If their habitat is disrupted during their youth, populations can be wiped out.

Adding to their vulnerability is that females of many species, like the famous blue ghosts of the southern Appalachians, are wingless and can’t disperse far. If a population of blue ghosts is destroyed by logging or other disruptions, it won’t reestablish. Habitat destruction is one of the greatest threats to fireflies. Other hazards include light pollution from artificial lights and possibly insecticide applications for mosquito control.